What I learned taking college classes in prison

/I wish I had a copy of the original flyer for the first Inside-Out class at the University of Oregon. I remember the moment with exceptional clarity: it was posted in the stairwell to the Honors College, and I was on my way to history class. It probably said something like

Honors College Literature Spring 2007 Inside-Out class

Spring term we will be offering the first ever Inside-Out class at the University of Oregon. The subject of the class is literature by Fyodor Dostoevsky—we will be reading The House of the Dead and Crime and Punishment. The classes will take place at the Oregon State Penitentiary, with half UO students and half inmates.

Dostoevsky said “The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” Dostoevsky himself spent four years imprisoned in Siberia.

All interested students are invited to attend a mandatory informational meeting…

I read it and knew instantly I wanted to take the class. As I told my mom that evening, college is about gaining new perspectives, and I couldn’t imagine a more perspective-altering experience than reading and discussing literature in prisons.

UO students made a short documentary, Inside Looking Out about the second class I was part of. I highly recommend it:

The first time I set foot in the Oregon State Penitentiary, I had just turned nineteen years old. I had no idea that my entire life was about to change.

What prompted me to write this blog today was that a brief article about my experience with Inside-Out was just published by the Oregon Quarterly Magazine. I’m really pleased by the quality of reporting, and to be reminded of how far the program has come in Oregon. It also was a call to remember just how much Inside-Out changed my life, and the lives of many thousands of others who have had a mirrored experience to my own.

The Inside-Out Program started in Philadelphia, when Professor Lori Pompa shifted her criminal justice classes from touring prisons to actually meeting and talking with inmates. On the suggestion of an inmate named Paul, she developed a curriculum where these conversations could expand beyond a single day and into a semester-long class. By the time I took my first Inside-Out class in spring 2007, there were dozens of universities across the country offering classes with a mixture of “inside” and “outside” students, focused on dialogue and discussion, and dedicated to equality and transformation in the classroom.

Now there are hundreds of instructors trained across North America, and with movement further abroad.

I spent hundreds of hours in the Oregon State Penitentiary, first as a student, then as a teacher’s assistant and program coordinator. But that first day, on entering the prison, that Dostoevsky quote was certainly on my mind. What did this massive building say about our society? And how would I fit into the smaller microcosm of the classroom?

The first day of Inside-Out classes are largely dedicated to icebreakers and building trust in the classroom. It’s a dialogue-based class, so this sense of equality and sharing of opinions is crucial. We got to know one another. We discussed the text. We talked about literary techniques but also themes of justice and punishment and identity. We read Crime and Punishment and the inside students identified with the experiences Dostoevsky described in a way far beyond anything I could ever imagine from my own background and perspective.

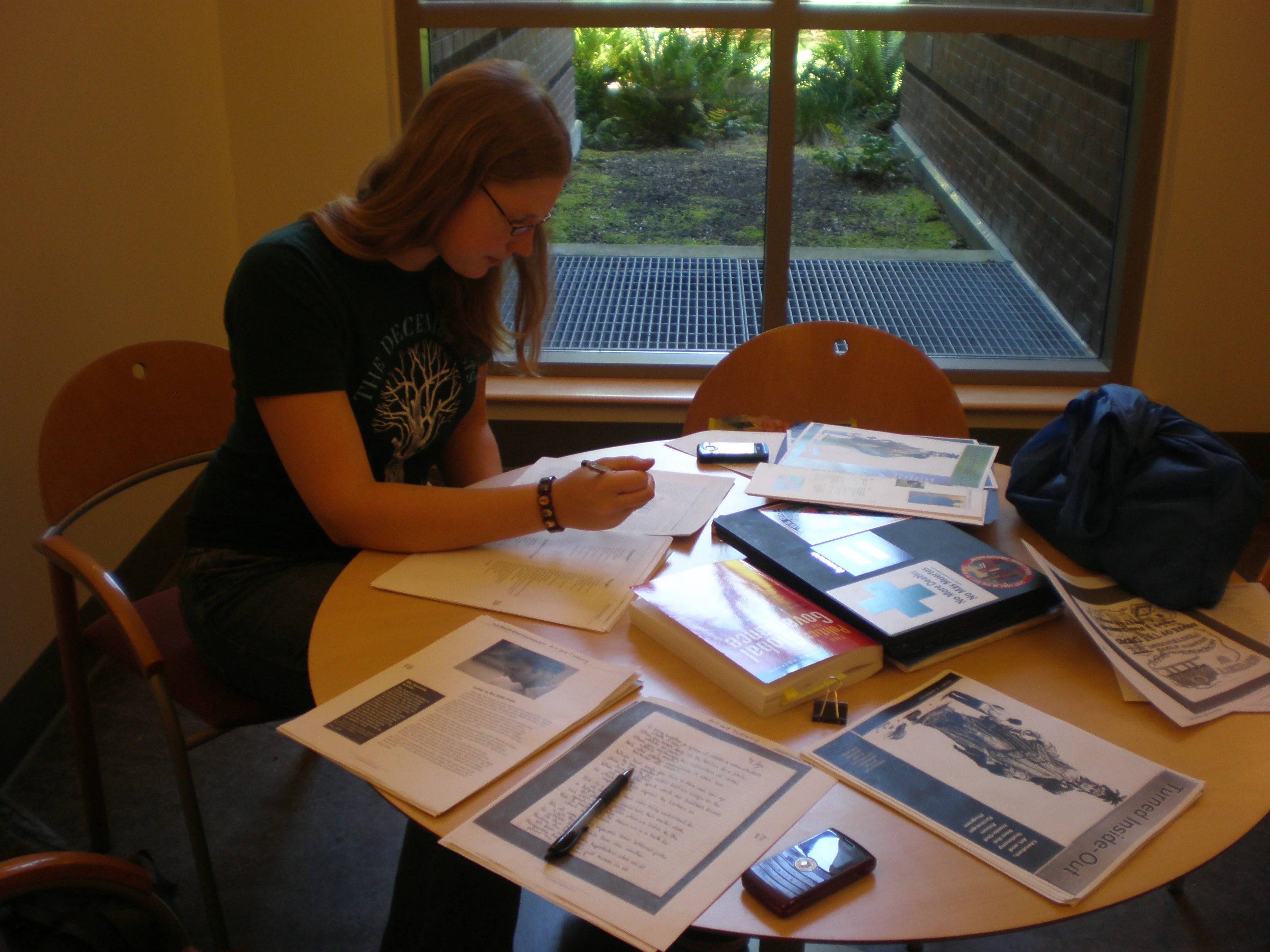

Inside-Out geography class "Divided Cities" Winter 2012 with Professor Shaul Cohen.

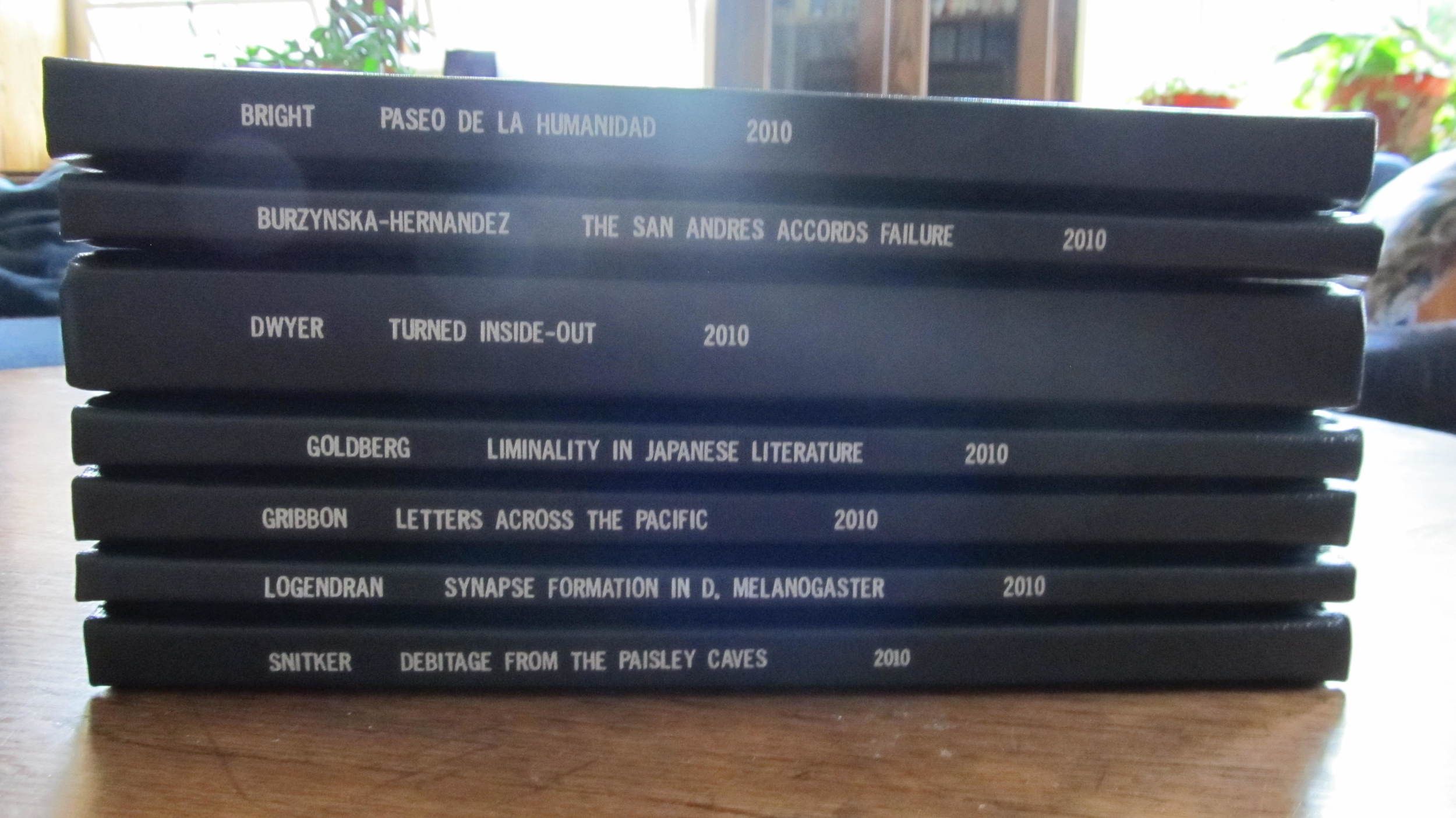

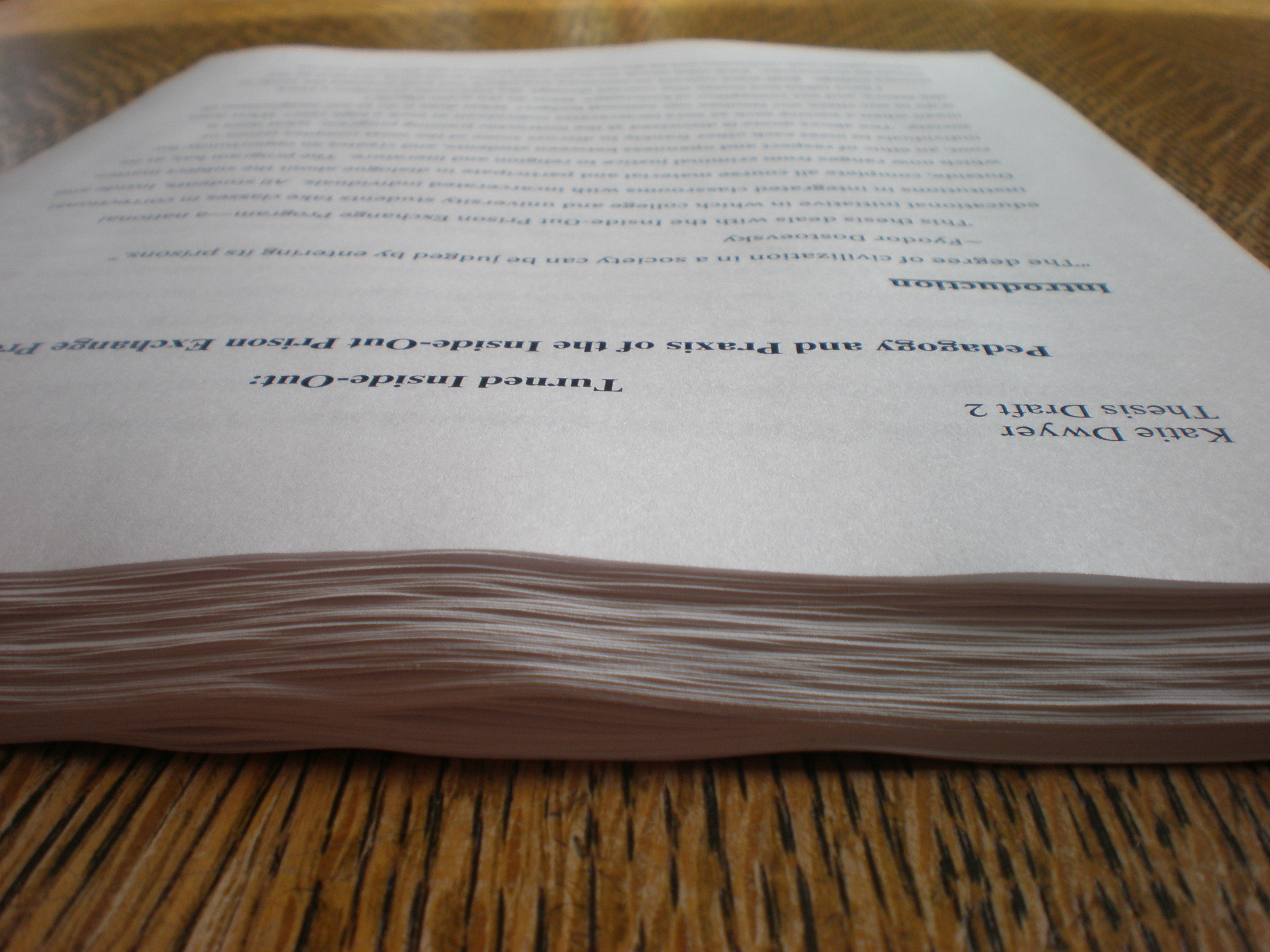

I was so profoundly impacted by these experiences that I sought out other ways to be involved and to engage with prison education issues. I wrote my undergraduate thesis on the pedagogy (teaching methods) of the Inside-Out Program. I created and edited a literary magazine from student work, alongside another UO student and an inside student at the prison. I created a discussion group at a local juvenile detention and, along with a team of other Inside-Out students, ran a weekly “book club” that started well and has flourished under the leadership of others. I went to Philadelphia to be trained as an Inside-Out instructor, and my senior year I began mentoring professors who were new to the program to help them teach Inside-Out classes and to deal with the complexities of curriculum, logistics, and relationships with the prison administration and staff.

I answered a flier on the wall of a stairwell my freshman year, and at that moment I felt I had found a calling.

Sometimes in life we hit these moments where an opportunity arises and just feels right. Inside-Out was that situation for me. It put to use my love for literature and dialogue, and my growing passion for social justice and off-the-beaten track experiences. Nothing in my life has challenged my opinions more, and nothing has offered me a more profound alternate view of the power of education and dialogue.

The key things I learned from these classes in prison:

The extent of my privilege in my identity

The power of dialogue

The connection possible through shared study and guided discussion

The critical importance of education

The problems in the US criminal justice system

A glimpse of the reality of prison life and the difficulties faced by those with criminal records

The opportunity to connect, even when perceived differences are enormous

The power of a small group to create a community

My own power as a facilitator and leader

How much I have yet to learn

Most of the lessons I learned by studying in prison had little or nothing to do about prison. They had more to do with the intensity of an experience that brought so many different kinds of people together in one classroom: not just inmates and university students, but people of widely different ages, backgrounds, race, education, and life experiences. I learned more about myself in those classes than in any other experience, and more about my place in the world than in any other time in my life. The closest thing to Inside-Out in my life has been study abroad. Engaging in dialogue with people at the prison shook me to my core. And isn’t that what education is all about?

As a note, many of the other outside students who took the class have gone on to continue to engage creatively with these areas. Some are

Working for Teach for America

Involved with the Peace Corps and Americorps

Education lobbyists

Student-body presidents

Long-term volunteers around the world

Teaching English abroad

Perhaps the kind of student interested in Inside-Out is inclined this way anyway. But I suspect that an encounter of this kind changes people, and pushes them to take action and engage differently with the world around them.

For those of you interested in this kind of program, I highly recommend you check out the Inside-Out website and find out if your school is offering classes.

But more broadly, I encourage you to stop and read the fliers. Find out what’s happening on campus, and pay attention when some opportunity or idea gives you a sense of wild potential and profound interest. Even if it’s something you never imagined yourself doing. Pay attention to the part of you that wants to break out of the expected pattern. Whatever it is, I hope that some random Tuesday you are confronted by an opportunity this momentous in your life.

When that time comes, I hope you say yes.

Related articles: "Inventing an Internship," "Networking: My Belfast Case-Study," and "On Choosing a 'Useless' Major," which was written by my Inside-Out classmate Miles Raymer.